Chapter 1 Writing My Way Out of My Mother’s Shadow

How writing sheds light on the scars left behind by my mother and the invisible cruelty of covert narcissism.

Over two months ago, I embarked on a journey to reveal the extent of harm inflicted by my mother.

To put it lightly, the weeks leading up to the creation of my first and only published work — my prologue — were filled with complete and utter dread.

I remember the day I started as though it was yesterday; the first few paragraphs were written beside my dad at his dining table. Soft, ethereal melodies filled the air, and sunlight beamed brightly through the windows as he worked on his artwork.

As I opened my laptop, the familiarity of the small confines of a digital screen greeted me. It had always been a refuge while living under my mother’s roof — it offered an element of control over my emotional stability where there was none (you could call this dissociating). Yet, whether I was gaming, watching movies, or completing professional work in my bedroom, I constantly felt as though I was under threat — to be doomed at any moment.

The anxiety in my stomach and the sporadic nature of my fast-paced mannerisms (which I now know to be fight-or-flight) stripped me of all opportunity to experience any joy and remain present with what I was engaging in.

Writing has allowed me to focus on something new for myself for the first time seven months into seriously addressing my trauma. And as words began appearing on my screen, I noticed something.

My fingers floated over the keys with grace, and the world around me fell silent as my body and mind became one.

There was no unease, no pressure to do or be any particular way, simply a state of just ‘being’. This complete serenity and centeredness provided a pathway for my imagination to become colourful again.

I then experienced a sensation in my body that was so unfamiliar and ancient that I couldn’t even name what it was.

Then it hit — I was taking pleasure in enjoying something.

The muscles in my arms started to tingle, fiery flashes pierced the back of my neck, and a soft warmth blossomed in my chest.

I was met with an intense wave of nostalgia as my mind reached into the depths of my childhood.

I started to remember what it was like to try new things without feeling a sense of existential shame. Beautifully painful emotional flashbacks and memories of being alone with my dad as a young boy began to surface. I remembered the encouragement that the simple presence of his aura gave me in the face of failure — a time that presented opportunities and freedom to find my own footing and discover who I was.

Within seconds, I was suddenly overwhelmed, and I burst out in an instinctive glimmer of vulnerability:

“Wow! I’m actually a good writer!”

My head shot up in excitement, and I glanced over at him. His face was already gleaming with one of the biggest smiles I had ever seen.

In shock, I explained what was happening inside, although he already knew. He stood up to embrace me warmly in his arms and began to cry as he held me tight.

Conflicting emotions swirled as I confronted yet another acknowledgement of my mother’s dark nature and the extent of how much time I had lost under her reign.

“Scapegoating a child goes against the grain of most of our schemas of parenting, and even humanity.” — Jay Reid.

Parents hold a sacred responsibility in this world — to help their children thrive.

This can come in the forms of many, including but not limited to:

Recognising and celebrating a child’s individual qualities.

Taking delight in their happiness.

Nurturing their authentic selves by validating their thoughts, beliefs and feelings.

A covert narcissistic parent, frankly, does the opposite.

Driven by a desire to feed their false sense of superiority, they inflict wounds by slowly eroding their child’s sense of self through relentless blame and belittlement.

Think death by the tens of thousands of kicks of a bunny rabbit.

Inevitably, this fosters an environment stripped of empathy, where the child feels perpetually marginalised and misunderstood. This leads the child to grow an internalised, deeply entrenched belief that they are only worth something if they suppress their true nature.

In this dynamic, the narcissistic parent then actively seeks to convince the child that they are as flawed and unworthy as they are offering themselves to be. The parent then views any attempt by the child to assert their self-worth or confidence as a direct challenge to their authority.

It Got Worse When Dad Left

I had already developed many unconscious strategies to comply with my mother throughout childhood, but whatever chance I had remaining was gone once the emotional safety net of my dad left the family when I was twelve.

Now, being the sole male in the household, I was left to face her abuse alone while looking out for my little sister.

No longer was there room for my emotional needs or the individuating of my authentic personality. Instead, I was so focused on navigating survival that I had no energy for much else.

Here lies the birthplace of my cPTSD and the split I formed that snowballed over the years as a psychological defence — my very own slice of her pie — covert narcissism (albeit traits).

I coped by replacing the belief that she couldn’t love me with the idea that my worth was tied to my productivity.

If I wasn’t being productive, I was worthless.

Every action I took and every decision I made felt like a direct reflection of my mother’s opinion of me.

This constant measurement became a routine, leaving me suspended between my own identity and her emotional needs.

Jay Reid, in his book ‘Growing Up As The Scapegoat To A Narcissistic Parent’, describes this strategy as a method of reclaiming hope for the scapegoated child. The hope is that if the child can ‘do right,’ then the parent may have a change of heart.

By following this approach, the child gains enough psychological breathing room to feel that the situation is fixable, allowing them to continue functioning.

However, the drawback is that the child is thrust into an endless loop of trying in the face of perpetual failure.

The child doesn't dare to believe that their parent is abusive — that isn’t even in their vocabulary. Believing such a thing would mean death.

But how does this relate to your blog, I hear you ask? Well, now we’re getting to the good stuff.

Being a Survivor of Emotional Abuse Is Fighting Daily Battles in Your Head with Someone You No Longer Have Contact With

Many hours have been spent buried under the weight of my cPTSD since my prologue was released, remaining stuck in a chronic freeze-response under my duvet for days and heavily dissociating at the thought of getting behind my keyboard and repeatedly facing reality.

Having the ability to be able to now safely say something that is true for me and aligns with my authentic self to describe how I feel is traumatising on a level that I never knew existed.

Emotional flashbacks attack my body as I brace for the inevitability of my mother’s downgrading and demeaning nature through every word.

Despite being in the warm comfort of my home, my body is adjusting to the fact that what I’m writing about is not happening in real-time.

Getting out of bed almost felt like taking the first steps out of the trenches and into no-man’s-land, warily opening my draft and finding the will to sit through a few sentences.

Within minutes of starting, I enter a panicked frenzy and instinctively perfect all the chosen words of the previous day.

I’ve been conditioned to focus intently on even the smallest of my mother’s cues. Her passive-aggressive gestures, her contemptuous eye glances and all the subtle nuances through her tone of voice

My lens has fine-tuned itself to these signals over the years but is now focusing on her ghost as my corrosive inner critic takes the forefront of my psyche — all the punctuation marks, the careful selection of each word, and the tone of every sentence.

I ensure it is said delicately to avoid any possibility of retaliation through a mistake or incorrect explanation of things. Otherwise, I’d be unsafe in my body. Then, the world becomes unsafe. I have to be safe.

This trauma trait has been a spine throughout my life, revealing itself in everything I do, whether it is relationships, hobbies, or professional work.

During interviews, when asked the familiar question, “What can you bring to the table?” I always intended to mention my perfectionism and would hang on to that.

For many years, I knew, deep down, that my mother had given me this trait — but I never realised it had its roots in darkness.

For a long time, I had been subconsciously trying to gain my mother’s approval through what I could do ‘for her’ behind the keyboard— a futile attempt that left me feeling hopeless about validating my self-worth.

Scapegoated children are forbidden from knowing what they are good at. To do so would be to defy the narcissist’s contention, which would risk ripping away any remaining self-esteem or pride.

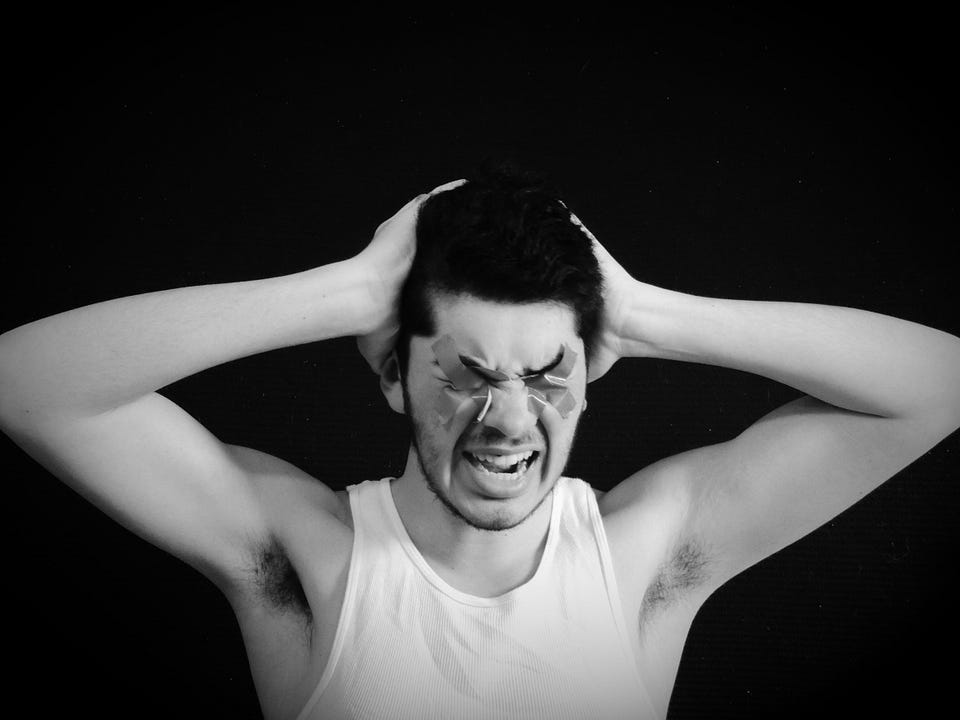

Each writing session would inevitably prematurely end with me hysterically crying, banging my fists on my lap, desk, or head, and screaming concoctions of: “What the fuck, Jacob? How can you not even do this right?”

I sporadically jump from behind my desk, manoeuvring around the house like I’m on the comedown from escaping a bear chase. I make a cup of tea as my vision goes blurry — my amygdala is on fire.

My shaking hands drop the tea bag on the floor, and a wave of toxic shame envelops me.

“You can’t even make a cup of tea. How can you expect to live in this world?” I hear my mother exclaim.

Her clever work on me has done wonders. Bravo!

When I realise what’s happening, I sit down and allow myself to feel. Then, the floodgates open; my chest implodes with grief, and I surrender to the horrific pain that is the maternal void, making sounds that seem as though they are coming from the scenes of a battlefield.

Anger is quick to arise as my veins boil, my fists smash onto the nearby cushions, and my inner child and adult self form a dance.

“How could you do this to me?” I scream repeatedly until he’s had his say. Many curse words have been uttered here; never have I ever felt so much hatred, abhorrence and resentment towards another human being — an experience that comes so unnatural.

Finally, feeling this anger has been the key to some of my recent breakthroughs. It has restored a lot of my power and allowed me to create the words that you’re reading freely and without doubt.

Anger is a healthy emotion and a natural response to abuse. That kind of anger is called righteous anger. Righteous anger tells you someone is hurting you, and you must act. This kind of anger is meant to motivate you to do something so that you stop allowing that person to hurt you.

Anger was one of the emotions that my mother shamed me for the most. There were moments when my body could not cope with her mistreatment towards me any longer, so I would retaliate, trying to preserve my humanity but with no prevail.

She liked to threaten me with exile and always, always needed to have the final word. There was nothing I could ever do to be heard — no amount of logic or reasoning would suffice.

It’s a perpetual setup for failure.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. I have lived through some of the calmest, most present days of my existence since leaving her grasp.

Yet, despite all this, I sometimes feel so much empathy towards my mother once I’ve followed the flow of my feelings. I see all that she could have been, but isn’t. It’s the ultimate trauma bond.

Thank you for making it to the end and giving me your time today. It truly means the world.

Please consider giving me a follow and clapping the story if you relate to it ❤️

The way you describe what you suffered and the way your mother functions, has stayed with me for days. I have a better understanding of what it must be like for a child to live under a narcissistic parent...argggh

I’m so sorry this has happened to you Jacob. So courageous of you to be writing about your experiences, really proud of the man you are growing in to, keep going . All my love 🫶🏽❤️xx